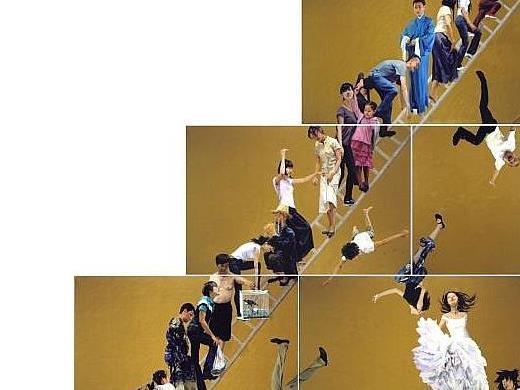

Ladder to Heaven by Hong Yu

The Minister for Education Christopher Pyne has announced the review to consider whether the current system ‘meets the skill needs of the economy’.

The review will also consider whether the demand-driven systems is increasing participation in education and improving access for students from low socio-economic status backgrounds and rural and regional communities.

The Minister has denied he plans to reintroduce the cap on university places but surely a government either provides the funds for whoever wants a tertiary education and is qualified to receive one or doesn’t, in which case there is a cap whatever you call it.

Under the demand-driven system, the Government funds Commonwealth supported places for all domestic undergraduate students accepted into a bachelor degree course (excluding medicine) at a public university.

Announcing the review, the Minister expressed concerns that quality was suffering at the expense of quantity, following the removal of the cap and the introduction of the demand-driven system in 2012 by the Labor Government. The inquiry will consider whether there is evidence of any potential adverse impacts on the quality of teaching and of future graduates as a result of increased numbers and will ask what measures being taken by universities to ensure quality teaching is maintained and enhanced in the demand-driven system.

The Minister seems then to have answered his own question about the degree to which the result has been increased participation in the Terms of Reference for the Review, noting that the introduction of the demand-driven system has seen the number of Commonwealth supported places increase from around 469,000 in 2009 to an estimated 577,000 in 2013.

So we can assume that the questions regarding the needs of the economy and the access for disadvantaged groups of students will be at the heart of the inquiry – and given the political colour of this government my money is on concern about economic value ahead of equity.

The Government is appropriately concerned that expansion in higher education both enhances the knowledge and capabilities of Australians and delivers quality graduates who are able to contribute to their society and thrive in the global economy.

But the danger is that if knowledge, capabilities and contribution to society are too narrowly defined, creative arts – along with pure science and much of humanities – will be sacrificed to a short-term vision that sees universities as factories for producing doctors, lawyers and accountants.

Despite ongoing work to measure the value of the arts in social and economic terms and excellent evidence of the transformational power of the arts in education, creative fields are inevitably vulnerable to any attempt to quantify or contain learning. Such restrictions are particularly problematic when they attempt to use purely economic criteria to justify contribution to society.

If the universities inquiry focuses on graduate careers, it will inevitably find universities are producing creative arts graduate who are not employed directly using the skills they acquired at university. It may, if it looks more carefully, find people who deliver creative thinking in other careers whether in the burgeoning applied creative sector or more broadly in business or the professions. It probably won’t find the people who are enhancing their own lives, their relationships and our society through bring music or beauty or original thinking into our lives.

There is, of course, an argument that the Government should not pay for any of this, that it should only pay for pragmatic applied education to deliver people into needed careers and that all the rest are frills.

But to argue this is to dismantle the university model and replace it with a narrow functionalism that would impede are growth both as an economy and a society. The very word ‘university’ is derived from the university’s place in providing holistic learning, producing men and women with trained minds to apply to whatever life throws at them rather than merely training to do a technical job.

In an age when tomorrow’s careers are yet to be invented we need to avoid second-guessing and narrowing educational options as a way of saving money.

Education is expensive and it is inevitable that a Government which has come to power on a platform of a platform of budget stringency will be looking for savings. But picking winners among 18-year-olds and leaving an increasing proportion of students without access to tertiary education is no way to enhance the creativity or robustness of an economy.

If Christopher Pyne is committed to not reintroducing the cap but is unhappy with the cost of places driven by demand his other option may be a cap-by-stealth, through lowered subsidies and increased university fees. The Howard Government Minister for Education Dr David Kemp and his former advisor Andrew Norton have been appointed to run the inquiry. As Minister for Education Dr Kemp supported a demand-driven system but also argued, in a leaked Cabinet submission, for the abolition of HECS to be replaced by a loan-scheme and for an open market that would lead to higher tuition fees.

Such an outcome would have a similar effect to a cap, privileging professional courses where students could afford to borrow on the promised of generous salaries ahead of creative or ‘pure’ education.

Those concerned about the creative arts economy and particularly the arts education sector would do well to participate in this conversation.

The full Terms of Reference are available from the Review of the Demand Driven Funding System. Written submissions should be emailed to DDSreview@education.gov.au by midday (AEST) on Monday 16 December 2013.