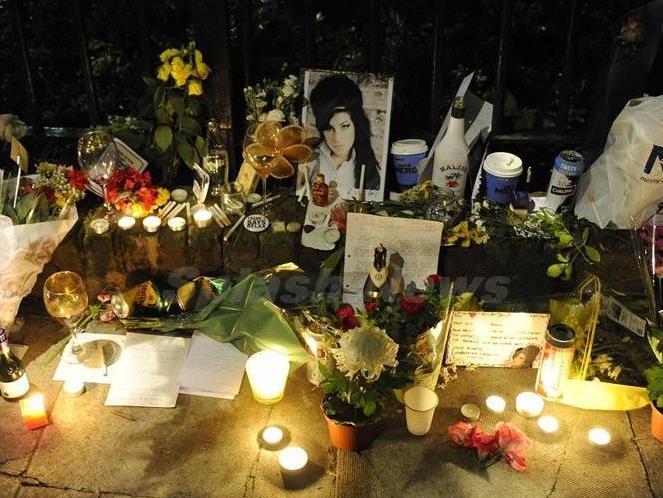

Image: Tributes to Amy Winehouse. Source: SplashSplash

The death of a public figure who we’ve never met, but whose work has had an impact on our lives, can take its toll. Much like the death of a friend or family member, the moment you realise that this person who existed in your periphery will never be there again can have a real psychological impact.

In the social media age, the way we grieve the death of an artist or celebrity has changed into what some people perceive as competitive grieving. Pinterest pages are devoted to deceased artists and people seem to want to ‘break’ the news or the death online before anyone else.

There wouldn’t be many Facebook users whose feeds weren’t filled with tributes to Lou Reed this week, and people will surely remember recent, similar tributes to author Iain Banks, musician Mr Yunupingu of Yothu Yindi, and author and illustrator Maurice Sendak. Yet social media cannot be blamed for our apparent need to collectively mourn these people; to almost celebrate our sadness. Instead social media is simply a tool we use for something we have always done.

In her Washington Post article ‘Tweet it and weep? Online, grief over dead celebrities is about us’, Monica Hesse writes: ‘If grief is a meme, it’s not a meme only on Twitter. Our need to publicize sadness goes beyond the online realm, which is why Buckingham Palace wheezed with the pollen from flowers left by Princess Diana’s mourners, why Michael Jackson’s tear-stricken fans aimed themselves like homing pigeons toward Neverland. Kurt Cobain died in 1994, and armies of eighth-graders waited for adults to ask why they were wearing black arm bands, just so they could have the satisfaction of rolling their eyes.’

The cynics will say this type of grieving lacks depth and is more about our need to demonstrate our identity. However, this way of grieving could simply be a coping mechanism. People looking for support for the sadness they feel over the death of someone they’ve never met may find their cries falling on the deaf ears of those who deem them trivial, which is why they band together with others who feel the same way.

In her piece, ‘Grieving Cory Monteith and Why Celebrity Deaths Are So Devastating’, Michelle Konstantinovsky writes: ‘Inevitably, people will argue over the triviality of our societal obsession with celebrity. But as tempting as some may find it to belittle the unrequited fascinations many of us have with famous faces, it’s impossible to deny anyone’s instinctual human response to death and loss.’

Psychologists call this one sided relationship with celebrities, artists and fictional characters ‘parasocial interaction’. The concept was written about as long ago as the 1950s but in an age of increasing media saturation and fictional characters who we develop long standing relationships with, it seems like people are becoming more and more involved in the lives of those who don’t know they exist, or who who don’t exist at all.

Kansas State University cognitive psychologist, Richard Harris, a professor of psychology who focuses on mass communication, told Science Daily that we lack the support structures for grieving the loss of a media character.

‘Somebody’s real upset that their favourite soap opera character was killed off yesterday and they tell someone about that and they laugh. It’s a very different reaction than if their grandmother had died.’

There an additional psychological term that describes the connection we feel with the famous. It is called ‘basking in the reflective glory’ or BIRGing. This is when we feel connected with a successful person, and as a result we feel good when they succeed. It’s extremely common on the sporting field; we experience elation when our team wins because we feel connected to them. But artists are similar – we feel that their work speaks to us, is an identity marker of who we are. When they receive a good review we feel happy, but the flip side of this is that when tragedy occurs, we experience it too.

The death of a local celebrity can be particularly dramatic. Australians felt the death of Heath Ledger acutely because we were proud of ‘one of us’ doing so well overseas. We felt a personal tie to this individual we had never met.

Publicising this grief then, is a natural extension of us basking in their glory. We need to let people know of our connection – we are Australian (like him); we watched him in Two Hands before his international success; or perhaps we feel a connection to Western Australia, where he came from. This is just one example, but demonstrates how we find ways to engage in this one-sided, yet very real, relationship.