With a new government in Canberra, the arts sector is understandably edgy about changing attitudes to the value of arts in society. What can we learn from the way arts policy has changed elsewhere when governments change?

The British experience may be instructive. In her most recent book, Artificial Hells Claire Bishop examines UK arts policies, beginning with the election of the New Labor party in the UK in 1997.

The first question the New Labor Party posed in terms of ‘art’ was: What can the arts do for society?

The question was related to the necessity for the Labor Party to justify national arts budget and display accountability for that expenditure. Bishop observes that the discussion which followed the New Labor challenged produced answers for measuring success such as: ‘increasing employability, minimizing crime, fostering aspirations – anything but artistic experimentation and research as values in and of themselves’.

As a consequence, the delivery of arts programs were reshaped in order that they would fit into government’s funds, which justified the support of art projects only if they were framed into the process of ‘social inclusion’; in other words, artists had to demonstrate that their projects would support ‘marginalized sectors’ in society and that their artistic approach would enhance the problematic of the marginalized community selected.Bishop claims that a buried intention behind the New Labor Creative and Cultural Policy was the elimination of ‘disruptive individuals’, particularly those who were reliant on the public purse, not only the welfare system but also who were receiving government grants to fund their own creative pursuits.

The new ‘social inclusion agenda was then ‘less about repairing the social bond than a mission to enable all members of the society to be self-administering, fully functioning consumers who do not rely on the welfare state and can cope with a deregulated, privatized world’.

In Bishop’s analysis the neo-liberal idea of community wasn’t seeking to build social relations, but rather to erode them.

Since the Conservative-Liberal-Democrat coalition came to power in the UK in May 2010, the agenda was accelerated, fostering a ‘new culture of voluntarism, philanthropy, social action’ where institutions sought to attract wage less volunteers to work in important services relating to education, welfare and culture to replace staff lost by shrinking budgets.

Policy in the UK, both in its initial New Labor form and as adopted by a Conservative government, sought to integrate artists into a system where they had social responsibilities. The restructuring of the concept of participatory arts transformed art projects as vehicles for the government to control and forced artists to pre-define concrete goals in order to receive government funds. By altering the criteria for the funding of arts projects, artists were in effect forced to become quasi-social workers.

This changing status for artists has been remarked on by many analysts. Sociologist Andrew Ross describes artists as the ‘No Collar’ workforce, since artists work project by project and accept less money in return to relative freedom. François Matarasso – a researcher with 25 years experience in community-base arts development- observes that social participation has been positively accepted because it encourages citizens to look after themselves ‘in a face of diminished public services’. But Paula Merli observes that the outcomes of these communit-based ats projects is to help people to accept their structural conditions and not to change them.

For a long time now, Australia has embraced funding the arts for social causes. One only needs to apply for any art grant to realize that it is obligatory to stipulate the social scope of the project and how it will positively affect the social bond in the community. These requirements force artists to work in the social field in a non-defined relationship between social worker and art. The project must be developed with a low budget that excludes wages for extra-collaborators such as: sociologists, social workers, etc. Therefore, artists are required to invest much time and effort to source volunteers who enable them to complete the project, and sometimes, the artist’s fee, which is already low, is sacrificed.With the Abbott government committed to constrained spending and yet to announce an arts policy, it is important that the pros and cons of policies that fund the arts only on condition of their community work are openly discussed in order to strike a balance between artistic experimentation and the requirements of the State.

If the main aim of government’s grants and art programs is to ‘support communities’, and to fund more effective ways to bring this support, then the payment of fees for external collaborators to the project and a greater level of freedom for the artist should be taken into consideration.

As the funding system currently operates, there is the danger that the artwork is transformed into a social program, delivered on a very low budget, and the artist is required to provide services that were previously government funded while the government in large part absconds itself of its responsibility to the community.

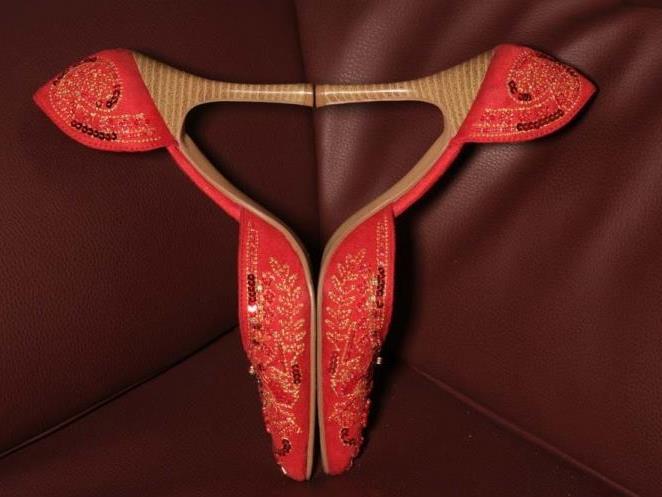

Image: Ramon Martinez Mendoza: from his series Hearts.