The twentieth century novelist and chemist C. P. Snow is most famous for a lecture that he gave in 1959 called The Two Cultures. In it, he described encountering a gulf of animosity and mutual misunderstanding between the worlds of the humanities and the sciences, both of which he was part of.

The same unfortunate gulf exists between the worlds of art and money. Artists have traditionally been uncomfortable with wealth and cynical when business invests in the arts – although they are happy enough to take the money.

Even in this age of relationship-building and corporate citizenship, many artists remain distrustful of the world of business. Often artists don’t understand, respect, or trust ‘brand’ or ‘community contribution’. They see business as only about making money and feel misunderstood and undervalued for their core creative work.

Slowly, business and the arts are learning to value one another for the pragmatic benefits that each gains. As Jane Haley, former CEO of the Australia Business Arts Foundation (now amalgamated into new entity Creative Partnerships Australia), pointed out on ArtsHub recently, ‘Businesses value partnerships with the arts that can enhance brand, engage employees and demonstrate community contribution. The arts benefit from business resources that support growth, promote sustainability and build resilience.’

But there is still a sense among artists that money is something dirty and unpleasant and that business is a necessary evil. Artists like to think of themselves as bringing insights the business world does not have: they are the wise fools, Shakespearean jesters spruiking truth to power.

Even our terminology divides us. While businesses speak of value, return on investment, and performance indicators, artists have their own jargon that excludes the uninitiated. Terms such as ‘visual dynamism’ and ‘the problematic of aesthetics exploration’ are not welcoming concepts for the uninitiated.

It is easy to be sceptical about the attention that business pays to the arts. Businesses necessarily, and properly, always keep the bottom line in the corner of their eye, and even with the best intentions, business funding of the arts cannot help but be at least in part an exercise in marketing.

But at the same time business does, actually, support the arts – the money is real money. Many people who are in businesses genuinely like art and enjoy their role in supporting it. We don’t raise an eyebrow when a business keeps a budget for corporate lunches or hospitality: so why are we suspicious, as artists, when some of their money is earmarked for us?

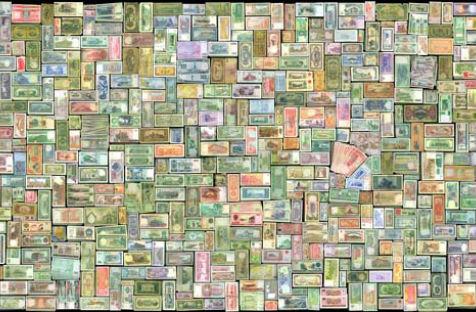

There is, of course, an old tradition of arts patronage in business but it tends to be restricted to certain art forms. Think of the centuries-long relationship between the fine arts and banking , typified by the Italian Renaissance and the lavish spending of the Medici family which financed Michelangelo, Leonardo and Raphael.

Film has a comfortable relationship with money. It seeks investors, not handouts, and looks to the example of blockbusters that bring in fortunes.

But many other artists feel uncomfortable with those who can and do provide financial support. Making money as a fiction writer is often regarded as an indictment of literary prowess– witness The Da Vinci Code and 50 Shades of Grey , and the best-selling author of the Harry Potter books J.K. Rowling has spoken about her discomfort with her unexpected wealth.

Somewhere at the bottom of the scale are the poets, who are barely on speaking terms with money. The trouble runs both ways, too: poetry, after being ignored for so long by so many, is often willfully obscure and affectingly defiant to any sort of commercial imperative.

Who are we kidding? Businesses and arts have so much to offer one another, it’s time we stopped treating business as a necessary evil, and started regarding it as a genuine partner in the creative industries. Put down your paintbrush and hug a suit; business and the arts were made for each other.