Board games are booming. Article after article describes a “golden age” or “renaissance” of boardgaming.

In Germany, the home of modern boardgaming, the industry has grown by over 40% in the past five years; the four-day SPIEL trade fair this year saw 1,500 new board and card game releases, with 209,000 attendees from around the world.

What is it about board games that attracts people, and what emerging trends can we see in the latest releases?

Board games are booming with young adults. Shutterstock

Social, challenging, real

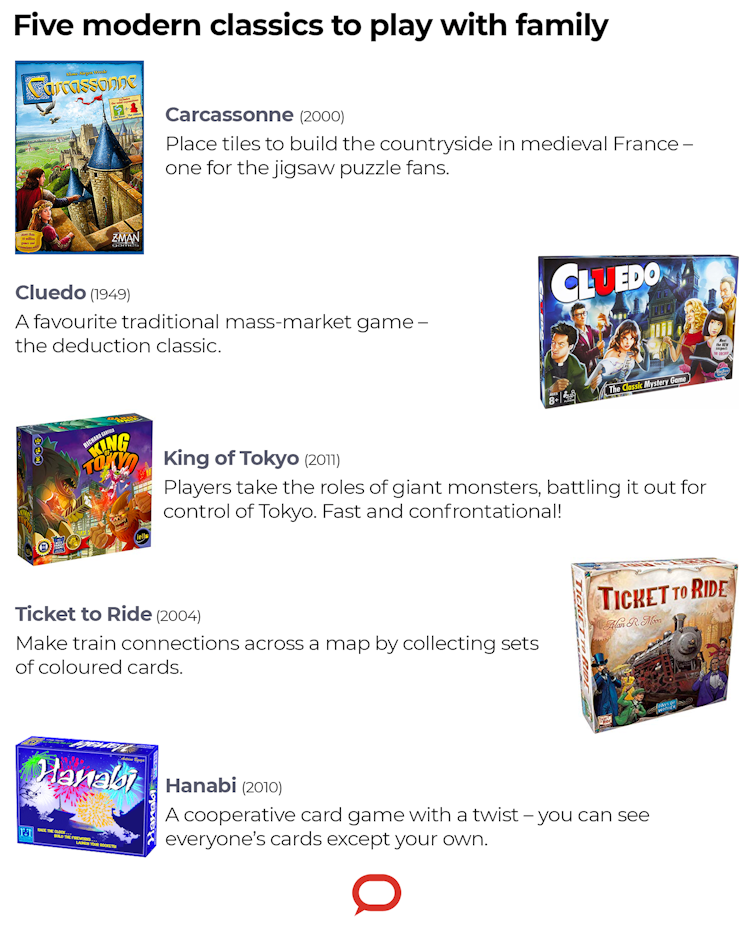

Four main elements make board games enjoyable for families and dedicated hobbyists alike.

Firstly, board games are social; they are played with other people. Together, players select a game, learn and interpret the rules, and experience the game. Even a mediocre game can be fun and memorable when you play it with the right group of people.

Secondly, boardgames provide an intellectual challenge, or an opportunity for strategic thinking. Understanding rules, finding an optimal placement for a piece, making a move that surprises your opponent – all of these are enormously satisfying. In many modern boardgames, luck becomes something that you mitigate rather than something that arbitrarily determines a winner.

Thirdly, board games are material – they are made of things; they have weight, substance, and even beauty.

Hobbyists speak of the tactile joy and sensual delight of moving physical game pieces, and of their appreciation for the detailed art on a game box or board. Some go to great lengths to protect their games from damage, even “sleeving” individual cards in plastic to protect them from greasy fingers, spills or wear.

Collectable Monopoly sets and other vintage games can fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction.

Finally – and this helps to explain the enormous volume of new releases each year – board games provide variety. Beyond “the cult of the new” lurks a desire to have the right game for the right situation – whatever combination of gamers and strategic depth that might require.

The game’s theme matters, but so do the mechanisms of its play, as well as the game’s expected duration. Like authors, game designers such as Pandemic creator Matt Leacock attract a following of fans who enjoy the style of games that they produce.

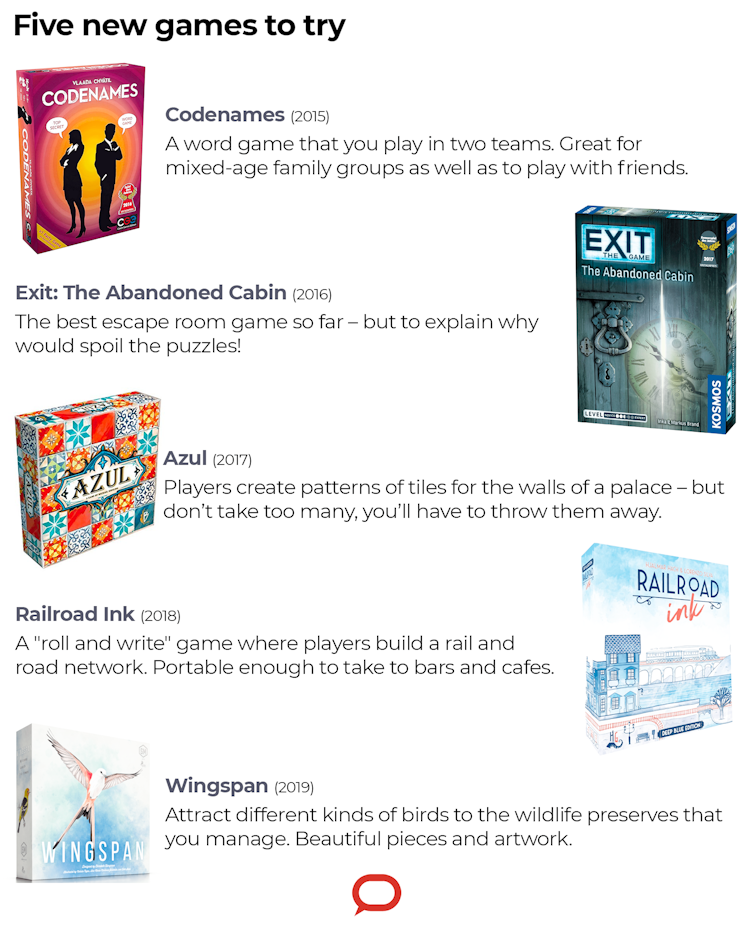

‘Escape room’ experiences

To meet the demand for variety, designers look for new elements to offer in their games. “Legacy” style games – where players customise the game as they play it, writing on the board, and discarding rules or game components – create a one-off, individualised variant of a core game. They also invite a group to play together over several play sessions, modifying “their” game throughout the experience.

That can feel confronting to those of us who grew up protecting our games from “damage”.

If writing on game pieces is confronting, the Exit game series, by German couple Inka and Markus Brand is even more so.

These small, inexpensive games aim to replicate the experience of an “escape room” experience by providing the players with a series of puzzles to solve together, as a cooperative activity. To solve the puzzles, however, players must literally destroy the game – cutting up cards, tearing objects, folding and gluing and writing on them.

Board games are not fading away in the digital world. They are booming.

There’s a lot to be said for these low cost single-play games, which build communication and teamwork skills and – like real-world escape rooms – provide an opportunity for friends and families to work together to solve a common problem.

For those who would like to be able to retrace their steps, or to pass a game on to friends, the Unlock! game series takes a different look at the escape room genre by using an integrated app to provide clues and answers.

This ensures that the game itself is replayable, even if the players do not wish to revisit the same story.

Like Exit games, the Unlock! series offers creative opportunities to combine different objects as part of solving the puzzles, but adds occasional multimedia elements and uses the various properties of a smartphone as problem-solving tools.

Real boards, digital play

For people who enjoy solving puzzles, there are many other new games that combine digital technologies with the components and feel of a board game.

Chronicles of Crime puts players in the role of police detectives, who must travel to different locations to interview suspects, consult experts, and conduct searches.

Similarly, Detective sets players to solve a series of crimes. In this game, however, it is not enough to simply learn who committed a crime, it also must be proven by the chain of collected (and registered) evidence registered by players on a custom website.

These games reflect the broader development of a small group of games that use digital tools to add new features to board games.

One Night Ultimate Superheroes uses an app to run the game, taking on an administrative role that would otherwise have to be performed by a player.

The Lord of the Rings: Journeys in Middle-Earth uses an app to speed setup, set game maps, resolve rules and track the players’ progress, streamlining and simplifying play.

Beasts of Balance – a simple, dexterity-based stacking game – uses an app to create a story world which brings the tabletop animal figures to life and encourages players to stack different figures to continue its narrative.

These digital tools add variety to the range of boardgames that are available. More than simple battery-enabled games like Operation, they provide new ways to interact with the game material and mechanisms while still supporting the sociability, intellectual challenge and tangibility so enjoyed by players.

Physical board games aren’t going anywhere, but apps add exciting new possibilities to this play space.![]()

Melissa Rogerson, Lecturer, School of Computing & Information Systems/Interaction Design Lab, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.