Image: Shutterstock

These days all text is digital. From writing an email to publishing a new edition of War and Peace, text nearly always exists on a computer first. Yet there are writers who take full advantage of the computer’s possibilities, utilising new technologies to broach complex subject matter.

Electronic or digital literature does not refer to e-books, but to works that depend on electronic “code” to exist. Put simply, you can print an e-book, but you cannot print electronic literature.

Within the field there is emphasis on experimentation. Many works are the result of authors simply trying new things out and seeing what happens. Here, then, are ten significant works of electronic literature you should know about.

A digital love story

Alan Bigelow’s How to Rob a Bank reinvents Bonnie and Clyde for the digital age. It can be viewed on a smart phone or in-browser. Users swipe the touchscreen or hit the space bar to reveal a narrative told through iPhone web searches, text messages, and app activities.

Critiquing a classic

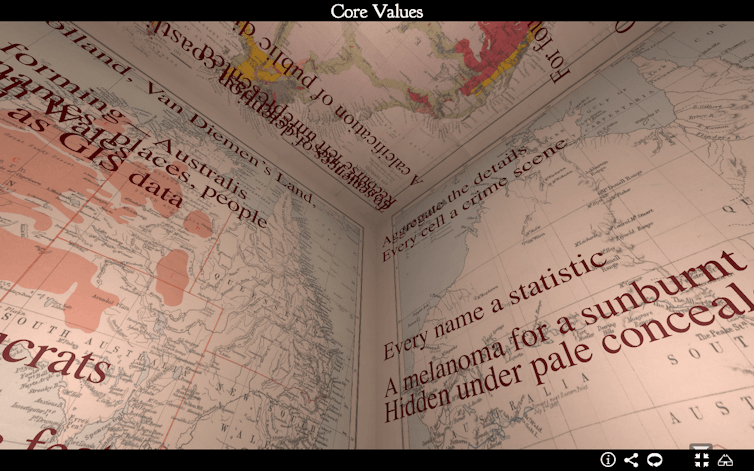

Digital poet Benjamin Laird wrote Core Values in response to Dorothea Mackellar’s classic Australian poem My Country. Laird’s work is displayed in a three-dimensional box, viewed in-browser or using a virtual reality headset.

Text is broken, animated, and infused with geographical coordinates and data. Unlike Mackellar’s “sweeping plains”, “mountain ranges”, and “flooding rains”, Laird’s poem evokes claustrophobia. It critiques Mackellar’s poem, creating an Australia where the reader feels trapped.

Benjamin Laird’s Core Values critiques the classic Australian poem My Country. Courtesy the artist

Rewriting AI

Montréal-based David Jhave Johnston produced ReRites, using artificial intelligence trained to imitate contemporary poetry. The AI generates text which is then edited by Jhave. Recordings show this process in real time.

Jhave’s ReRites.

Twitterbots

Piotr Marecki’s Cenzobot is a Twitter “bot” (an automatically generated Twitter account) that tweets fragments from real Polish censors’ reviews of publications from the communist era.

Marecki conceived of this project following the Twitter Bot Purge of February 2018. He suspects Cenzobot will also be purged. Indeed, it is the goal of his work.

An environmental statement

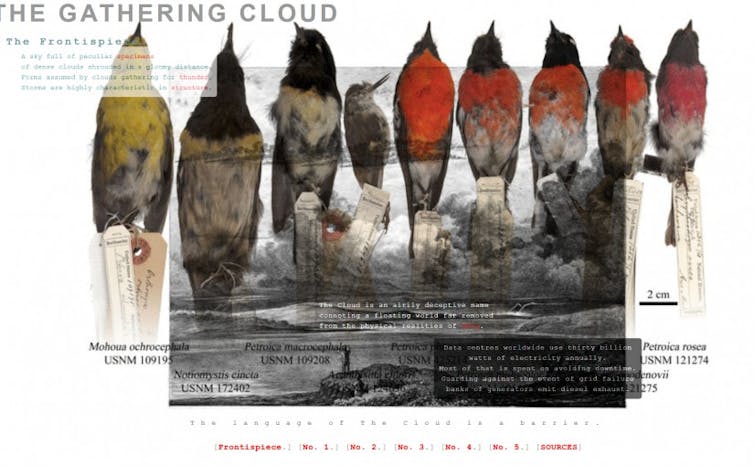

The term “cloud” computing emerged because clouds are perceived to be infinite resources. However, neither type of cloud is infinite, and few people acknowledge the energy used by large data centres. J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud tackles the environmental impact of “cloud” computing by calling attention to the clouds above us.

Fragments from Luke Howard’s 1803 Essay on the Modifications of Clouds are pared down to produce Carpenter’s poetic verses with hypertext links that users can interact with.

The poetry is accompanied by animations of animals, which bridge the link between clouds in the sky and “cloud” computing. A cumulus cloud weighs as much as 100 elephants. By indicating 100 elephants in animation, the full weight of “cloud” computing’s environmental impact is evoked.

J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud explores the environmental impact of cloud computing. Courtesy the artist

Political speech

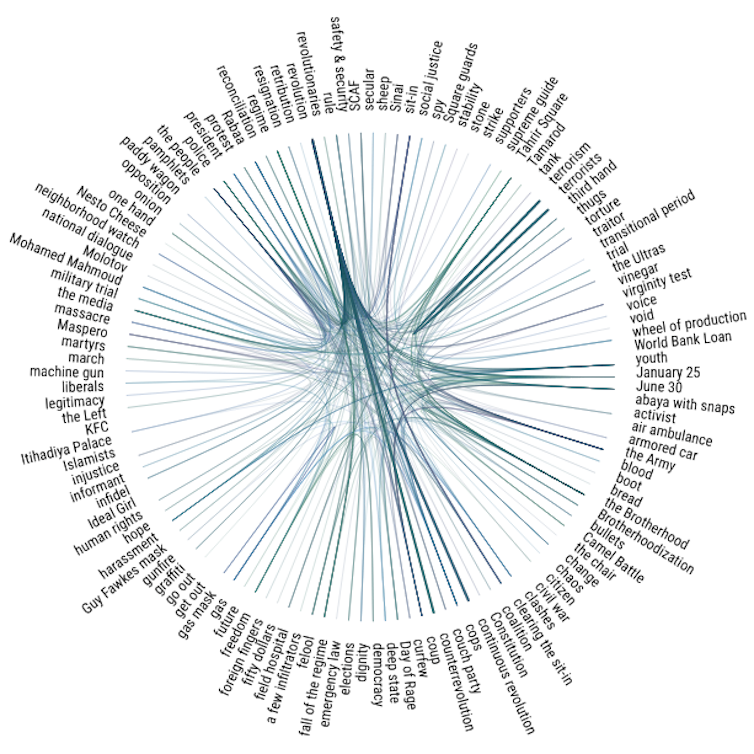

A Dictionary of the Revolution by Amira Hanafi is an experiment in multi-vocal storytelling. Hanafi created a vocabulary box containing colloquial Egyptian words. Hundreds of voices were then asked to define the evolving language of the Egyptian revolution.

Choosing cards from the box, subjects discussed what the words meant to them and how the words’ meanings had changed. This research informed the project that includes woven imagined dialogues around each term.

Users click on the word to learn the story behind its meaning. Each word is connected to several others, forming a linguistic maze users are encouraged to get lost in. A Dictionary of the Revolution is available in both Arabic and English.

Amira Hanafi’s A Dictionary of the Revolution explores the language of the Egyptian revolution. Courtesy the artist

A novel idea

novelling by Will Luers, Hazel Smith, and Roger Dean is a novel combining text, video, and audio, available to read on a computer.

The work arranges media fragments in six-minute cycles to suggest a narrative between four characters. The interface changes every 30 seconds, or whenever the user clicks the screen, creating an ever-evolving story.

Robot interaction

The Listeners by John Cayley is a third-party app that creates a work of spoken, interactive literature. It builds on the infrastructure of the domestic robot “Alexa” (it is also possible to experience The Listeners using a smartphone and the Alexa app).

The user begins by addressing Alexa, saying: “Alexa, ask The Listeners.” The Listeners responds, listening and speaking in its own way. The user may extend the performance by saying “Continue” or “Go on” or “I am filled with anger”. This work explores themes of surveillance, and the very notion of allowing a domestic robot such as Alexa into one’s home.

Poetry/fiction hybrids

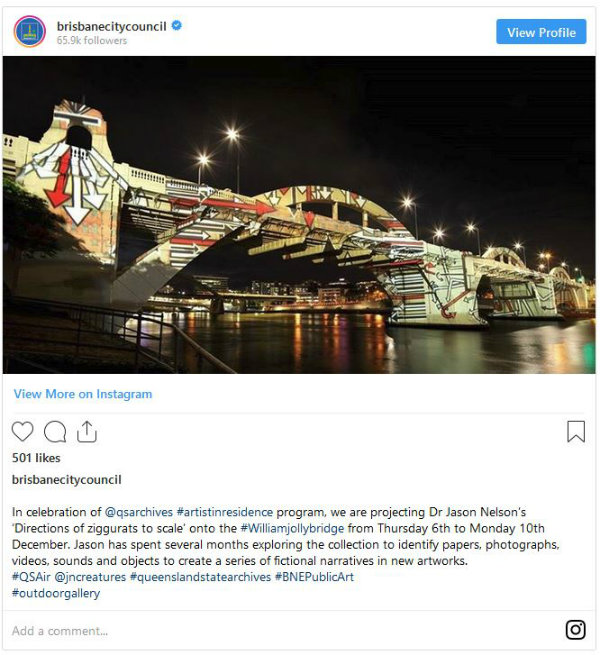

Jason Nelson’s Nine Billion Branches is a poetic narrative accessed online. Each page has numerous arrows, poems, and highlighted areas to read, play, and explore.

Nine Billion Branches is preoccupied with the poetry of the immediate world. Poetry exists beside photographs of escalators, garbage bins, and bedside tables. Much of Nelson’s recent work exists beyond the web, sometimes projected onto real buildings or landscapes.

Virtual reality

In the past decade, Mez Breeze has merged digital literature with virtual reality. In 2017, she created the virtual reality Poem/Experience Our Cupidity Coda, which can be viewed online or with a virtual reality headset.

This work emulates the conventions of early cinema. Just as early motion picture devices had the viewer look through a peephole window, the viewer (or reader) of Our Cupidity Coda is encouraged to treat the virtual reality headset in the same way.![]()

David Thomas Henry Wright, PhD Candidate, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.