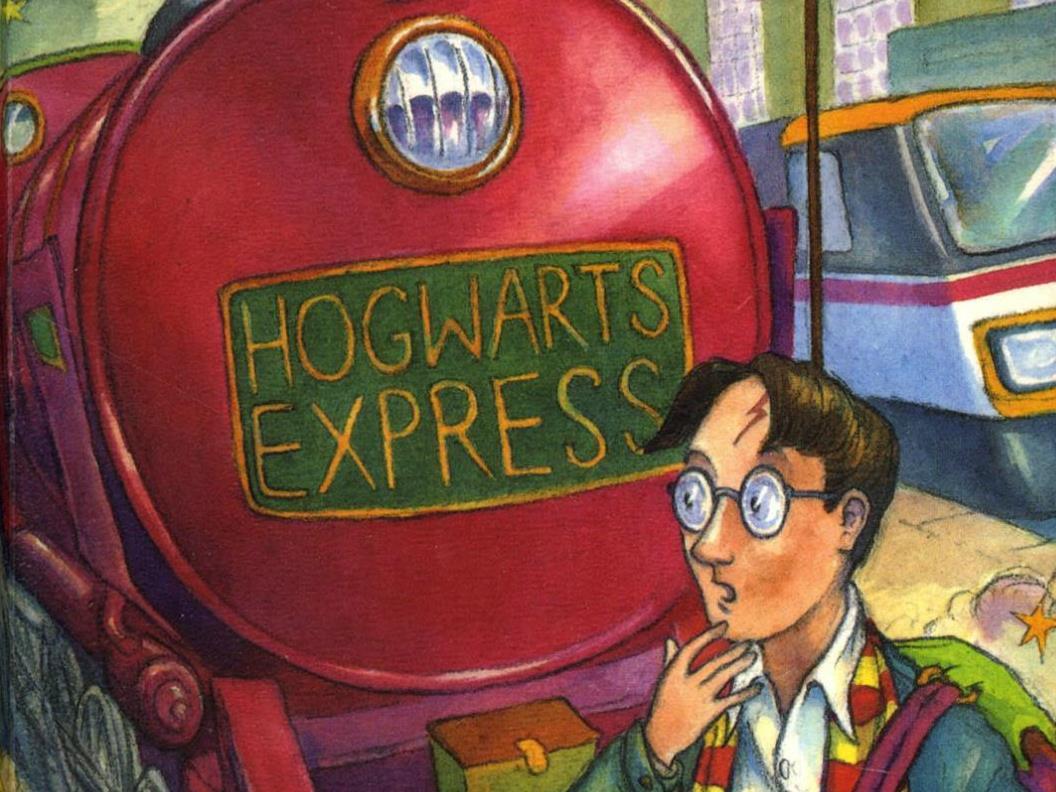

Image: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone cover art

On 26 June 2017, the world will celebrate the 20th anniversary of the UK publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first book in Joanne ‘JK’ Rowling’s phenomenally popular Harry Potter series.

Written at a time when Rowling was desperately poor, and grieving both her mother’s death and the collapse of her first marriage, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was rejected by at least nine publishers before finally being accepted by Bloomsbury.

Following the first book’s publication on 26 June 1997, what became the seven-part Harry Potter series (telling the story of the titular character, dubbed ‘the Boy Who Lived’ and his predestined struggle with the evil Lord Voldemort in a world of witchcraft and wizardry) went on to become a global publishing phenomenon, selling over 450 million copies worldwide and spawning an extremely lucrative film franchise.

More importantly, the books also inspired a generation to read. As hype around the series grew, the publication of each successive book in the series was punctuated by parties at bookshops around the world attended by eager children in costume; some of whom were so keen to re-enter the world of Harry Potter that the sight of young readers sitting on footpaths and in gutters, so engrossed in Rowlings’ writing that they couldn’t wait to get home before opening the book’s pages, became commonplace.

So what was the appeal of Harry Potter – and 20 years since the first book in the series was published, what is their legacy today?

Magical words

Rowling’s language and writing style were a critical part of the books’ success, according to Jan May, a spokesperson for the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English (VATE).

‘During the years when I was reading the first three books aloud to the youngest of my children, the language just rolls along – and the made-up words, the unique vocabulary that JK Rowling invents, the children just loved,’ said May, who now teaches VCE English at Firbank Grammar.

‘The alliteration and the assonance of words as you were reading too, you could really enjoy those – “Rita Skeeter” and “Severus Snape”. Even down to the names of the spells or the names she gives the characters, such as where the Dursleys live in Little Whinging; that always raises a chuckle,’ she added.

Writer, creative producer, and communications specialist Laura Hughes points to Rowling’s ‘relatable, genuine characters’ as central to the books’ appeal for herself and her peers when they were younger.

‘The books are written for kids, not at them. The people who, like me, grew up with the main characters still relate to them,’ she said.

The combination of familiar adventure tropes with a contemporary voice was another factor in the appeal of Harry Potter, said Joel Becker, CEO of the Australian Booksellers Association.

‘There is certainly an old-fashioned component of boys’ and girls’ own adventure told in a lively contemporary way with a strong moral compass in Rowling’s books,’ he told ArtsHub.

‘I think the books appealed across generations. Adults read it to younger children. As the kids got older they read the next volumes themselves, and the adults kept reading them for their own pleasure. For a time, they did adult covers, but then it became respectable for a grown-up to be seen on a train or tram with a copy of Harry Potter, so that appeared to be ditched.’

Program Coordinator at the Centre for Youth Literature, Adele Walsh, agrees that Rowling’s storytelling was key to the books’ multi-generational appeal.

‘I don’t believe that young people would have gravitated to the written word in the level that we saw with Harry Potter unless this one special story was created,’ she said. ‘But I think the fact that it was a series too – it grew with the reader, so they could start reading it as an eight or 10 year old as more of a junior fiction title, and then read it as it became YA – and then you could even argue that it became quite adult by the end,’ she said.

‘Her storytelling draws upon fantastical stories that people love. She’s created an amazing world – her world-building and the culture she’s created in her stories is vivid and it continues today, even 20 years after the books have been out there, but I think it’s her storytelling and her characters that people really sort of glommed onto.’

Enter Hermione Granger

In particular, Walsh points to the appeal of Harry’s muggle-born sidekick, Hermione Granger, as critical to the books’ popularity.

‘I think Hermione is really important in terms of Harry Potter’s success. Hermione isn’t the first book nerd in youth literature but I think she’s the one that really created a safe space for girls to identify as readers, and own it and claim it – and proclaim it. I think Hermione is a huge part of the success of the series and it’s no surprise that JK Rowling sees herself so much in Hermione. Harry is great, but I think Hermione is the secret ingredient, I believe,’ said Walsh.

The presence of Hermione in the books was also important for Hughes, who went on to become a writer herself.

”The first Harry Potter book was the second book I read that involved characters my own age – the first was Anne Frank’s diary. Both books ended up having a profound influence on me and my relationship to literature. Harry Potter had a nerdy girl as one of the main characters – I was so, so glad! The characters are relatable and – rarely, for a book written by an adult – sounded like my peers and I. The series didn’t necessarily influence me in becoming a writer, but certainly influenced my friends and I to read. Reading was cool because of Harry Potter!’ said Hughes.

The inventive marketing campaigns associated with the books was another important aspect of their success, according to Becker.

‘The marketing was absolutely brilliant,’ he said. ‘The simultaneous world releases; promotions like Gleebooks in Sydney hiring a steam train with 1000 passengers from the city to the Blue Mountains, with the books being handed out as they arrived at the midpoint of the journey (the Mountains) at 9am was genius. Watching queues of people waiting for a shop to open, and then sitting on the pavement unmoving for the whole day – not even waiting until they got home to read the book.’

Gateway to fantasy

Twenty years after the first publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone – for which Rowling was paid a £2,500 advance – what impact have the books had on their millions of readers?

‘Harry Potter had a massive impact on new fantasy genre writing,’ said Becker. ‘It also had people revisiting Tolkien. I think the success of the books and films for Harry Potter was a game-changer for the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings franchise.

‘Interestingly I think it also wound up having a major impact on the dystopian children’s and YA fiction that followed. Most importantly it made reading cool for a whole generation – maybe even two generations,’ he said.

Walsh agrees, noting that books such as the Percy Jackson series, Divergent and The Hunger Games have clearly built on the success of the Harry Potter series.

‘YA [Young Adult fiction] has become part of the zeitgeist and in a large part I think that’s because of the Harry Potter readership growing up and reading more,’ she said.

The impact goes beyond reading, Hughes added: ‘Having worked in publishing I can definitely confirm that even in 2017, everyone is still trying to write the next Harry Potter. The genre of fantasy was reborn with the Harry Potter series, bought out of the geeky shadows and into the mainstream.’

Beyond their impact on reading and publishing culture, the popularity of the Harry Potter books appears to have directly impacted on literacy levels in Australia. In 2002, the NSW Education Department’s then Deputy Director-General (Schools), Alan Laughlin, credited the books for rising literacy rates in the state, noting that because of Harry Potter, children had begun to see reading as cool. ‘Literature is no longer seen as the province of the nerd,’ he told Fairfax.

As an English teacher, May has seen the impact the Harry Potter books had on students – and her own children – firsthand.

‘The first book in the series my father actually bought for my daughter, who must have been about seven or eight at the time … We’re a family of readers, and this child just devoured this book in about two days, and then gradually it was spreading through all her friends too,’ she recalls.

But it wasn’t just the popularity of the books that made an impact – it was that they made reading a shared, social event, where the story of Harry, Hermione, Ron and their friends could be shared by people of all ages.

‘I was teaching through the secondary levels at that stage and it just gradually caught on – and the power was phenomenal. You had students reading, you had teachers reading, you had parents reading, you had children who couldn’t yet read on their own who were having it read to them,’ May explained.

‘You would read the book and find out what had happened next –and then you could talk about it with people, and it was just terrific … and because of that cross-over power to adults as well you could share the books as a family,’ she added.

Some critics of the books have dismissed them as lacking in literary merit, a claim May vociferously disagrees with.

‘Look, all you want is to see children reading, and when you see how they are devouring these books – and the themes in the books too. You have these three tight-knit friends, and the adventures they have and the choices they have to make in their lives; the way that they have to adapt to survive, to get along with other people – there’s so many affirming ideas being explored in these texts,’ she said.

Increasing empathy

As well as encouraging reading for pleasure and a corresponding impact on literacy, the books have had another, remarkable impact – they have made children more empathic and caring.

As documented in the Journal of Applied Psychology Volume 45, Issue 2 (February 2015), a study led by Professor Loris Vezzali of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy demonstrated that among children exposed to Harry Potter passages relating to prejudice (such as a scene where young villain Draco Malfoy, a wizard obsessed with ‘blood purity’, calls Harry’s friend Hermione a ‘filthy little Mud-blood’) their previously negative attitudes towards immigrants and refugees were found to be significantly improved.

Responding to this study, Walsh said: ‘They noticed within a week that the kids who had read the bits where people were being called “mud-bloods” and Hermione was being persecuted, that their behaviour got better and their empathy grew – which is kind of incredible!’

The complex themes of the books have equipped children with the skills to respond to the world around them, she continued.

‘I believe it’s made young people more politically aware. It’s given them the facility to look at the world and make correlations between current world events and what was happening in Harry Potter,’ she said.

As the books’ fans have grown up, some have taken those lessons to heart.

‘That advocacy is really interesting in terms of the Harry Potter community – you look at the Harry Potter Alliance in terms of all the good that they’re doing in the world; they’re using their love of Harry Potter to contribute to those with less, so I think it’s been a positive impact on many levels,’ said Walsh.

She also acknowledged a less serious but no less joyous impact the books have had on society at large.

‘Quidditch – the world wouldn’t have had quidditch and real-life World Quidditch Cups if Harry Potter hasn’t existed. I think seeing grown people run around as a snitch has really brought more to the world,’ she laughed.