At first glance, Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess seems simple, charting the unglamorous battle of man and machine over the course of a weekend.

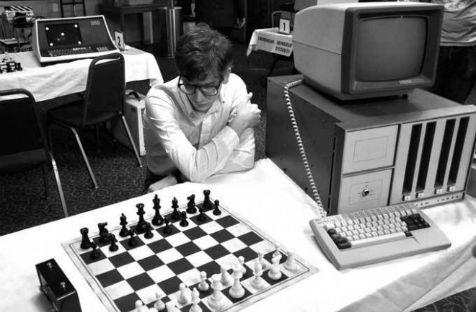

Immersed in the titular game in the early 1980s, the film follows those whose labours have improved their fields, their computerised creations, and the decreasing boundaries between them. Yet, as programmers adjust and argue, and their programs test expectations, the feature reveals its complexity. Beneath the lo-fi aesthetics and observational technique simmers something less ordinary.

In mumblecore hits Funny Ha Ha, Mutual Appreciation and Beeswax, the writer/director has previously proven his subversion of the straightforward; in Computer Chess, he adds an extra layer of authenticity. Styled for the era it depicts and seething with the strategy of its central game, the film both endeavours to document the most niche of subcultures long before their tastes gained acceptance, and adopts the object of their obsession to fashion the content into an enigma. The fiction of the events depicted is evident, yet the fidelity inspires questions. Performances are so pitch-perfect that they further provoke believability.

Three awkward personalities guide the narrative: the forlorn and frustrated Beuscher (Wiley Wiggins, Waking Life), the overt and eager Papageorge (Myles Paige, Funny Ha Ha), and the quiet but crafty Bishton (Patrick Riester, in his first feature role). With enormous computers in tow, they invest their sense of selves into the tournament, anxieties bubbling as their individually-designed chess programs fight for supremacy. The thrill of winning drives all three, but underneath lurks the joy of belonging. For one weekend, surrounded by likeminded but similarly eccentric coders, the trio of contenders are in their element.

Accordingly, what commences as a basic chronicle of the championships soon becomes something more, as characters swiftly but subtly blossom. Mirroring the group on screen, the audience warms to their amusing idiosyncrasies – engaging with their efforts to find accommodation, anger at being beaten, and awe at the lone woman (debutant Robin Schwartz) in their midst. The creation of artificial intelligence provides substance to their story, as demonstrated in meandering but meaningful discussions. And of course, there’s chess in abundance – the pieces forever moving around a board, just as the players circle around the hotel.

Yet, it is Bujalski’s uncanny throwback style that proves the pivotal piece of the production, inventively employing equipment from the period to immerse its narrative in distorted monochrome visuals. The concept is inherently comedic on sight, but its minimalism masks the intelligence of cultivating excitement from the unlikely, as does its commitment – and that’s the essence of Computer Chess.

Rating: 3.5

Computer Chess

Director: Andrew Bujalski

US, 2013, 92 mins

Sydney Film Festival

June 5 – 16