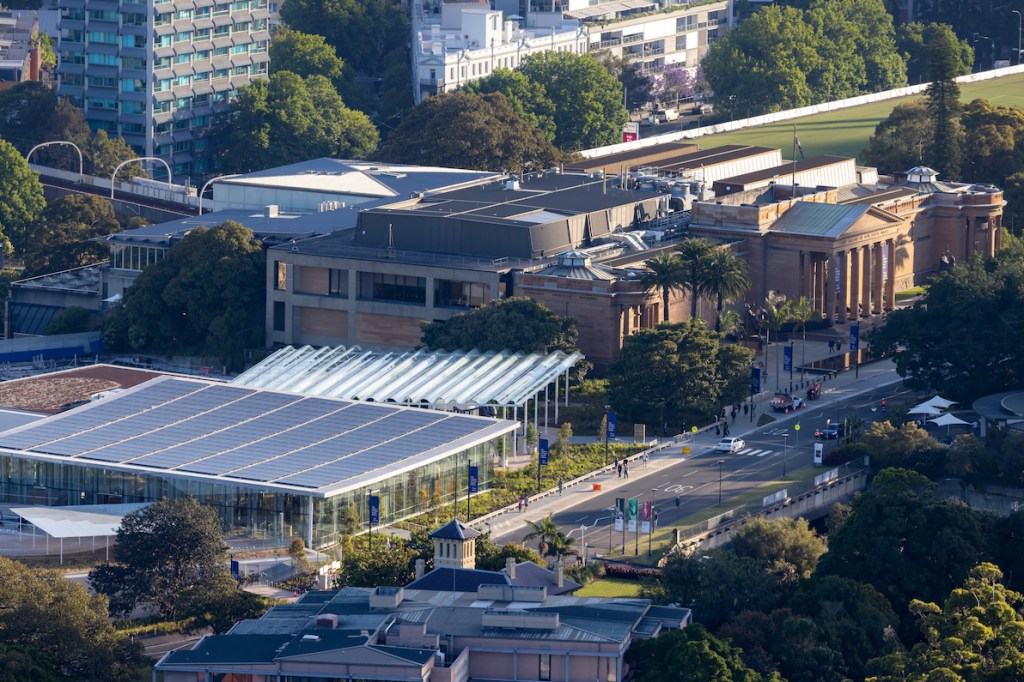

On time and on budget was the message across a swag of events this week to mark the opening of the Sydney Modern (for this story, SM), which will officially welcome the public this weekend. The free, ‘destination venue’ cost $344 million, with the NSW Government contributing $244 million to the project – the largest spend in the state since the building of the Opera House, and largest public private funding mix in Australian history for a cultural asset.

During the opening events NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet told media: ‘You need to have imagination, and I think this art gallery today is all about imagining a brighter future.’

We are told the free general entry will stick (though in future some temporary exhibitions will be ticketed), however the name may not.

Sydney Modern was designed by internationally celebrated Japanese architectural firm SANAA (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa). A gallery source told ArtsHub that while this has been the name used to describe the new space, the institution is currently in a consultation phase to explore renaming both the Art Gallery of NSW and Sydney Modern as a single brand.

Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art didn’t seem to have a problem with it, and we have all got our tongues around the QAGOMA acronym, so what’s wrong with SMAGNSW (aka smag-ness), then?

It feels like it is a conversation that could have been resolved over the new gallery’s decade-long build, rather than a kind of blurry question mark over ‘the campus’ – a term also being used by gallery staff.

The gallery’s map for visitor navigation merely describes the spaces as North Building and South Building. This is not the only thing that feels unresolved with the building’s launch.

For a decade now, Sydney Modern has been championed by many, and a thorny controversial fight for others. ‘Starchitecture’ aside, what does $344 million really deliver for visitors and curators alike, trying to hang in these light-filled, earthy spaces?

Great building, but does it work as a gallery?

Striding across the Welcome Plaza of SM, visitors are graced by three enormous, playful sculptures by New Zealand-born, Berlin-based artist, Francis Upritchard. They seemingly squeeze in under a form-cast glass canopy with steroid-sized corrugations that echo the ripples of the Harbour and outback architecture, and are said to be slightly tilted for natural cleaning. Time will tell.

While the canopy has been designed to sit just under the height of the old building as a sign of respect, the proportions feel somewhat overwhelming. The choice to position Pritchard’s work here over a First Nations artist – which has been a push in recent years across Australian galleries – is an affirmation from the outset that Sydney Modern’s outlook is international.

Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones will create an art garden also in a welcome position and linking the space between the two buildings, but it was not ready for the gallery’s opening. No explanation was given why, other than that the work will be revealed mid-2023. For such a strong key statement, this reads as a mistimed moment.

When the barricades come down around Jones’ piece, visitors will also be able to view from the Plaza 24/7, Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s Narrbong-galang (many bags) 2022, which hangs in the new Yiribana Gallery with a full wall of glass to the outdoors. A contemporary take on dilly bags for foraging, it is beautifully sited here.

Placemaking is important today for any cultural institution, but so is the visitor journey, and having diverse tones and narratives to usher people through it. Sydney Modern gets it right here.

First impressions and tone

One can’t help but subscribe to the infectious excitement and buzz in the air; the sector has waited for this building for a long time. Undoubtedly, the new gallery is world-class (and is the only gallery in Australia with a six-star energy rating) – but it also feels world-class.

However, as one steps over the threshold of SM into a vast, glassy atrium that adheres to the SANAA design signature, the first impression is of openness – not art. And, as the architecture’s awe moments subside, they are replaced with questions.

The empty entry foyer tilts slightly towards the Harbour and the centre of the building, blurring the inside and outside – in what Director Michael Brand has described as ‘democratising the waterfront’. However, that linkage with the Harbour, on first impression, is obscured by two massive lifts that run like a spinal column through the centre of the building.

The other initial whack on entry is the gallery shop – it is literally the first thing one encounters when stepping in to the building. A first-of-its-kind bio-resin installation designed by Akin Atelier, and produced from surfboard material fabricated in Sydney, its rosy glow has been celebrated for the warmth it offers to the building.

SANAA projects have been criticised in the past for their white-on-white boxes that ‘are strewn on the landscape or stacked, [and] lack local context’. For Sydney that local connection is found through materiality, such as the shop and, importantly, the gallery’s wall surfaces.

The 250-metre rammed earth walls pick up the tone of Sydney sandstone and offer a nod to the colonial façade of AGNSW, while 50,000 bespoke limestone ‘bricks’ surface many of the gallery walls. Therein lies a problem. Neither are easy surfaces to hang art upon, and in a need to control hanging, some areas start to have a real ‘lobby art’ feel.

A curator from AGNSW told ArtsHub that the vision for the larger lower atrium space (surrounded by those rammed walls) will be used more rigorously with curated sculpture in the future.

‘People don’t necessarily come to an art museum for an art history lesson. What we’re trying to do is provide a certain experience of not just art, but also architecture and landscape, with a really deep sense of place,’ Brand told The Art Newspaper.

The question for any gallery with a $344 million spend is: does it function well as a gallery – which should be its primary function? The short answer is ‘yes, but…’ The longer answer is a little more complex.

The Sydney Modern project has doubled the space of the gallery – a total new build of 17,000 square metres. Of that, 7065 square metres is exhibition space. Then that shrinks again, if we talk about running wall metres – the amount of physical hanging space.

- Art Gallery prior to expansion: 23,000 square metres (original building)

- Art Gallery after expansion: 40,000 square metres (new and original building)

- Exhibition space prior to expansion: 9000 square metres (original building)

- Exhibition space after expansion: 16,000 square metres (new and original building)

- Accessible roof ‘art terraces’ and courtyards: 3400 square metres

In this vastness, the actual gallery spaces are modest, and often cramped. For example, the two galleries presenting the exhibition Making Worlds feel overhung and congested. The content itself offers a really interesting proposition and dialogue, but a bit of breathing space would have helped pieces such as Mikala Dwyer’s work, which visually bleeds into the artworks that surround it.

However, the adjacent space, presenting Korean artist Kimsooja’s participatory installation Archive of mind, is stunning – an expansive, column-free space where audiences can meditatively shape clay while taking in a spectacular view of the gardens.

Other new galleries present the inaugural exhibition Dreamhome: Stories of Art and Shelter – a really strong exhibition that uses robust exhibition design and great storytelling for a next chapter. Then there is Outlaw, which is a modest exhibition for the new time-based art gallery. This gallery could have been more generous given a digitally immersive world today and the developments in new technologies that are increasingly shaping the global art landscape.

Lisa Reihana’s expansive video Groundloop takes centre stage of the new gallery’s atrium, hovering over a 11-metre drop. The use of this space is fantastic, and I love that you can sit in the gallery restaurant and slowly watch its unfolding.

And, of course, the talking point for many is Adrián Villar Rojas’ installation The End of Imagination in the reclaimed World War II fuel tanks. The work is an invigilator’s nightmare with its sharp surfaces and low light levels, but a brave statement by both artist and gallery.

Rojas’ five sculptures occupy the newly revealed 2200-square metre Tank Gallery, squeezed between 125 concrete columns, that rise seven metres high. Installations in this space will change every year.

‘I wanted to slowly reveal the space,’ Rojas told ArtsHub, adding that as a viewer you have to commit to that experience of not being in control and having ‘to let yourself be guided’ as choreographed lighting on moving tracks, offers fractured glimpses of the material and immaterial world he has created.

Of further note is Spirit House by artist Lee Mingwei, which sits outside the gallery in a custom-built rammed earth structure – and feels a little indulgent given the wealth of the gallery’s collection.

Of particular note, the new Yiribana Gallery is 40% larger than its prior space, moving from the bowels of the building to being the only gallery on the entrance level to SM – a manifestation of the gallery’s tone and vision.

Artist and Gallery Trustee Tony Albert told ArtsHub: ‘This gallery demonstrates how powerful art can be in its ability to heal and to transcend cultural, age and language, to educate and to challenge.’

He continued: ‘Let’s not be a part of history, let’s make history. Our colonial history is complex; it cannot be extinguished. But if we do not learn from our mistakes, we are going to make them in the future. We do not need to encourage alternative viewpoints, but implement and value Indigenous people, perspectives and knowledge … we do not need to tell the story of Indigenous people. We need to empower and open the front door to let Indigenous people tell their stories their ways.’

A nice touch also to Yiribana is another window facing the Harbour so visitors can see where the Gadigal ancestors witnessed the arrival of colonial fleets in 1788.

Dovetailed buildings and the verdict

This was a challenging site both for its topography and the fact that approximately 70% of the new gallery is constructed above existing structures – the land bridge built in 1999 over the freeway, and the subterranean naval oil tanks. For this reason, much needed parking and better linkage between the buildings, is a flaw.

Further, the former taxi drop area outside the old building has been subsumed by Kathryn Gustafson’s redesigned forecourt, with its two black granite reflecting pools (which are a little too similar to NGV International) an elegant statement, but at the cost of practical access.

While the AGNSW has spent the past two years refurbishing and rehanging many of its spaces for the unveiling of Sydney Modern – of particular note Karla Dickens’ incredible new commission for the vestibule of the colonial façade as part of SM commissions was an insightful choice – nevertheless, there is a disconnection between the two buildings.

Not dissimilar to Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), those hoping to visit both spaces will have to head outside – and into the elements – and walk down the street to visit Sydney Modern. There is a not a lot of expanded pathways here, and ArtsHub will be interested to hear how the less abled, gallery-going community rate the building’s accessibility (especially the stepped tiered art terrace).

That said, the building delivers an experience – and, in an experience and entertainment driven economy (which promises tourism dollars), it delivers completely.

‘It will bring in an extra two million visitors to the art gallery every year, [and] over the next 25 years it will inject a billion dollars into the state’s economy. The impact of this new building is absolutely significant and profound,’ concluded NSW Arts Minister Ben Franklin.

Over 14,000 visitors have already registered to be the first members of the public to experience the new museum.

And the verdict? While it is easy to both love and criticise these white cubes of light that tumble down to the Harbour’s foreshore – and in particular love their thoughtful sustainability credentials – it feels like a lot of adjustments will be needed for this building to deliver to the full level of its pricetag. It almost feels as if you go to AGNSW for the art and SM for the ‘arty Insta experience’ and your glam coffee moment.

Check out the opening weekend program for Sydney Modern. Sydney Modern is located on Art Gallery Road, The Domain, Sydney.

Opening weekend Saturday 3 and Sunday 4 December 2022

Opening celebrations 3–11 December 2022

Extended hours during opening celebrations 10am – 10pm