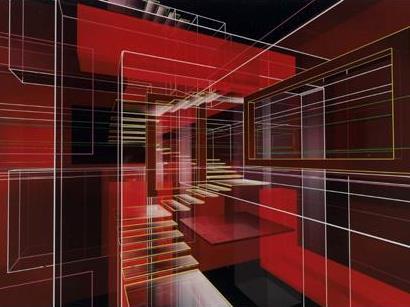

Peter Daverington, Spatial labyrinth, 2010, Image courtesy the artist and ArcOne Gallery

Stephen Bram’s work Untitled Two-point Perspective 2007 and 2008 in the JAHM exhibition of digital art consist of simple black and white rectangles filled with, in one instance, overlapping outlines of rectangles and squares, and in another, shaded rectangles and squares.

It is, to my eye at least, similar to much analog abstract art, the principal difference being that in Bram’s works the forms are ‘painted’ using digital files.

The works raise deep questions about the act of artistic creation: does the fact that the artist either created or acquired the digital files, rather than used his manual dexterity to paint them, matter? Has mental dexterity replaced manual dexterity? Is purpose, or the physical act of painting, more important? The works make me think about the way we value art.

Stephen Bram, Untitled (two point perspective), I2007. mage courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery

Jacob Leary’s The Sorting Process is evocative, to me at least, of Australian indigenous art. It consists of aggregated images sources from the internet and stitched together digitally. Does artistic creation, it seems to ask, consist solely of new images in a world awash with existing images?

Jacob Leary, The Sorting Process, 2012, Image courtesy the artists and Flinders Lane Gallery

Spatial Labyrinth by Peter Daverington conjures a space rather similar to that of a renovated warehouse. Flights of steps float, translucent in space, while columns and frames hint at structural elements. The overall sense is on an illusion – an Escher-like trick. Greg Neville’s Gooo-og manipulates an image from google earth to create an abstract image akin to the ornate stone inlay seen in some Indian temples, while Paul Snell’s Pulse #201021 is a series of concentric coloured rings which has been created through the deconstruction of digital photographs taken by the author. In its creative journey from complex to simple, it makes me think of the act of cremation or decomposition, for both processes take a complex entity and render it into simple molecules that can be used as the basis of new creations.

Ollie Lucas’s Neon Dispersion looks like a painted work of abstract art, but in fact it was created digitally. Once again, it forces one to ponder the boundary between digital and analog art.

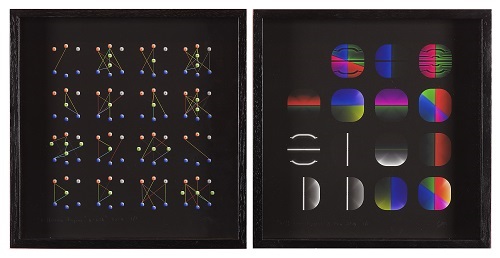

Gordon Munro is a mathematician who took up art in his 60s, and in his work the question of where creation lies in digital art becomes entirely unavoidable. That’s because Monro works by inputting mathematical formula into a computer, which in effect code for the artwork. His work thus becomes an investigation of artificial intelligence in the creative process.

This is particularly significant in the emerging world of digital art, wherein a digital ‘blueprint’, variously sourced, is used in conjunction with a machine to create art. In all but abrogating human responsibility for the work – beyond selecting which mathematical formula to input into the computer – Monro stands at one extreme of practice. His works 4.02a, 4.02b, have, perhaps predictably, a machine-like precision and patterning about them that reflects this method of creation. I find them extremely thought provoking, though unbeautiful.

Gordon Monro, Difference Engine 4.02a and 4.02b, Image courtesy the artist

Digital art throws up many questions beyond that of where the act of artistic creation lies. Purchase a work of digital art, and you are likely to receive a small box, inside of which nestles a nicely fetishized memory stick containing the blueprint for the work. I imagine that it’s quite a different experience from purchasing a canvas. And while a work on canvas can be stored away and only infrequently viewed, the digital work doesn’t exist until its digital information is manifested by a machine.

The high fidelity of digital art also sets it apart. It is the work of seconds to replicate with high fidelity the blueprint for an artwork stored on a memory stick. So what does it mean to own an ‘original’ work of digital art? Analog art of course faces its own issues in this regard. Photographs of works on canvas abound, but it takes a talented forger to faithfully replicate a painting.

In the newly emerging sharing economy, such distinctions may not matter that much. But in the existing world of conventional art, with its emphasis on authenticity, it presents a conundrum.

This article is an extract from the catalogue essay by Professor Tim Flannery for the exhibition DIGITAL- The World of Alternative Realities, now showing at the Justin Art House Museum- JAHM in Melbourne. To visit the exhibition, book via the JAHM website.