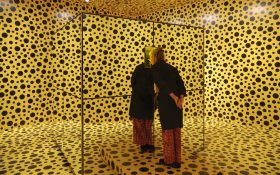

Magda Szubanski, photo by Konrad Winkler.

With a four-strand program, it was very hard to choose which sessions to attend. By the time honoured procedure of ‘sticking a pin in’ I chose Facing the Fear, which featured Jane Caro, Magda Szubanski and Rosie Waterland in conversation with Jane Cornes for the opening session. While the title looked somewhat ominous, the panel was, in fact, extremely entertaining, and in some spots, screamingly funny. How could it not be, with comedienne Magda Szubanski on the panel? One of Australia’s best known and most loved performers, Szubanski began her career in university revues, after which she appeared in a number of sketch comedy shows before creating the iconic character of Sharon Strzelecki in ABC-TV’s Kath and Kim. She has also acted in films (Babe, Babe: Pig in the City, Happy Feet, The Golden Compass) and stage shows. Her memoir, Reckoning is published by Penguin Australia.

Szubanski explained that she’d had a fling with a young man who turned out to be lacking in the baby-making equipment department and the ensuing repartee kept the audience in fits for the rest of the allotted timeslot. Szubanski went on to tell us that her mother was a Scottish Scorpio, and her take-off of that lady’s speech, complete with brogue, kept the laughter going.

Jane Caro is an author, novelist, journalist, broadcaster, columnist, advertising writer and social commentator whose work has won many national and international awards. Plain-speaking Jane is her memoir. Jane Caro’s Mum, a genuine Lassie from Lancashire, was a lady to be reckoned with. ‘Me Mum married oop,’ Caro explained in her mother’s native lingo. ‘Me Dad was Cambridge graduate’. She told us that living on Sydney’s North Shore and being no good at sport was not an easy life for a teenager. Did things get better? Well, her creative writing lecturer said she had talent, but she needed to get rid of ‘that feminist thing’! So where to next? Caro shrugged. ‘The phone will ring’.

Rosie Waterland’s childhood experiences made for chastened listening. Mum was a sex worker, and Waterland and her siblings attended some 17 or 18 schools and passed through a variety of foster homes. She has grown up to be a media phenomenon. Only 25 years old, she rose to fame in 2014 with her laugh-out-loud funny recaps of The Bachelor, which had people clicking onto the Mamamia website in astounding numbers. The Anti-Cool Girl, published by Harper Collins, is her first book.

After the all-female fun of Facing the Fear, it seemed fitting to move on to a gender-balancing item. On the Hearts of Men, with Jane Comes again in the chair, filled the bill nicely with its theme of masculinity.

The panelists related their feelings on masculinity to their backgrounds and their novels. Gregory Day, for instance, has military leanings. He is a writer, poet and musician whose debut novel, The Patron Saint of Eels (Picador, 2005), won the prestigious Australian Literature Society Gold Medal in 2006. His latest book, Archipelago of Souls (Picador 2015) tells of a hellish journey a soldier was forced to take after he was left behind after the Battle of Crete.

The panel also included Stephen Daisley, who grew up in the North Island of New Zealand and has worked on sheep and cattle stations, on oil and gas construction sites and as a truck driver, among many other jobs. His first novel, Traitor, won the 2011 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction. His latest novel is Coming Rain, set in the very masculine world of the shearing shed.

Lucy Treloar is best-known as a short story writer. Her short fiction has appeared in Sleepers, Overland, Seizure and Best Australian Stories 2013, and her non-fiction in a range of print media including The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, Womankind, G Magazine, The West, Visit Cambodia, RAM and Gardening Australia. Her first novel, Salt Creek, was published by Picador in 2015. Set in the Coorong distract of South Australia, it deals with the rather pig-headed efforts of a mid-nineteenth century man to tame the wilderness, and the struggles his family must endure due to the inevitable loneliness and isolation.

Three very different panellists with very different books. My ‘to-be-read pile’ grows apace.

My final panel for Friday, titled Call to Arms, gave me a new word – ‘cli-fi’, which refers to speculative fiction that deals with climate change. Peter Doherty, James Bradley, and Paolo Bacigalupi chatted with David Cohen on greenhouse emissions and the possibility of environmental calamity. If the worst-case scenario comes to pass, will humanity survive?

Medical scientist Peter Doherty expressed concern about food stress, water stress, the chance of nuclear war – all of which get a mention in his book The Knowledge Wars. He pointed out the possible connection between water shortage and the constant skirmishing in the Middle East. Paolo Bacigalupi felt that water shortage would eventually cause a rise in the number of refugees. James Bradley likewise sees current problems in Syria and stemming from climate change and water shortage. David Cohen pointed out that concern for climate change has become synonymous with Leftist policies.

An interesting discussion ensued in which it was suggested that we might have to choose between the less of two evils for a while – techniques generally considered dangerous, such as nuclear power, might have to be adopted while other possibilities such as wind and water power are developed.

The day continues

Artist as Activist, with Michael Cathcart as facilitator and panellists Ruth Little, Anthony (Tony) Marra, and Roman Krznaric was a discussion of how artists can make the world a better place by championing big issues and provoking empathic reactions.

Michael Cathcart asked Roman Krznaric, ‘Why ‘empathy?’ His reply was that he had been a political scientist, but he realised that what really changes people is being able to step into the shoes of the other. He emphasised the connection between empathy and the Greek ecstasis – stepping out of the self.

Tony Marra stressed that art can be used for destruction, not just creation, in answer to which Michael Cathcart asked what the difference might be between art and propaganda. Marra responded that it could be used either way.

Ruth Little suggested that we create on the basis of intimacy. It is difficult to harm or destroy anyone or anything once intimacy has been established. She felt that the element of ambiguity, which leaves things open, is important. She briefly raised the question of gender, suggesting that empathy might be more predominant in the female brain than in the male, which some might see as given more to competition, adversity and confrontation.

In response, Roman Krznaric said ‘There are two kinds of empathy, affective and cognitive, and what the individual does with them is more important than gender.’

Marra suggested that novels can open up a world to readers who would never otherwise be exposed to different people and cultures. That’s the role of empathy in literature.

Roman Krznaric quoted a zoologist who said that altruism is the most successful way to survive. He also called on the work of Franz Duval and his notion of homo empathicus. Our social institutions are designed for the serpent in us rather the dove. We humans need to rebalance that.

Michael Cathcart suggested that those of us who are more empathetic are dupes, always letting the bastards (the aggressive ones) rule us. Roman Krznaric answered, ‘But we are in the middle of a more horizontal development of our social and political organisation of society.’

Marra gave us an example from his novel The Constellation of Vital Phenomena, of a villain whom we come to understand as human by learning more of his background at the very moment –ironically – when he is torturing a victim. It shows how easily we can be turned into monsters.

Michael Cathcart said ‘Yes, it makes us wonder about the detention of refugees,’ to which Marra immediately responded, ‘These institutions pervert their very own missions and intentions. Not just the detainees, but also the guards and all involved are polluted.’

Ruth Little summed up by saying that we need all forms of ‘spection’ (intro and exo). We live suspended in the culture we have created. But artists can re-spin that web.

The next foray was to hear a talk about the Romanovs, surely one of the most celebrated and feared families in history, by London-based Simon Sebag Montefiore, who read history at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge. He is the author of Potemkin: Prince of Princes and the award-winning Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. He was interviewed by Bron Sibree on Russian leaders from Ivan the Terrible to Putin.

Bron Sibree set the ball rolling by saying The Court of the Red Tsar is ‘a monumental history’ resembling a family saga like Game of Thrones, to which Montefiore responded, ‘Yes, but not a family like any other. It is like Game of Thrones in that power taints and complicates all family relationships.’ He added that six of the last twelve czars were murdered.

After further questioning, he explained that he had always been interested in why Russia was so different – why it seems to have to have an autocratic ruler. Asked about his particular interest in Peter the Great, he replied, ‘Yes, he was a great moderniser – but Russian modernisers have never been like Westerners. For them it’s important to retain autocracy.’

According to Montefiore, Peter saw himself as a God-blessed czar, but he was mentally damaged. As a child, he had seen his uncles horribly murdered. He realised early on that a ruler can’t be fearful to the point of paranoia. Vigilant, yes, but totally in control. He tortured his own son to death and was always fascinated by gruesome things. He executed one of his mistresses, Mary Hamilton, subsequently using her severed head to give an anatomy lesson to the onlookers.

The influence of the East has always been present in Russia. (Genghis Khan, many Monghul-Tartar princelings, Czar Michael – an Islamic prince before converting to Christianity.) There have, however, been a few attempts at constitutional change, even on the part of the Czars. Alexander II brought in the liberation of the serfs, but other changes were not possible because as his reign got older he lost his prestige. Russia’s experience is that autocracy has always worked.

‘Autocracy,’ Simon said, ‘remains inscribed on the national consciousness’. He went on to say that democracy is not impossible, but more in the future – we must have hope, but Russia has always returned to autocracy after periods of social and political upheaval, as with Putin. Simon sees Yeltsin as noble and heroic, if not young enough to bring in popular change: his big mistake was in handing over power to Putin.

Bron Sibree mentioned that Putin has often been referred to as ‘half-Sta, half-Czar’. Montefiore agreed and went on to tell us that Putin’s office was Stalin’s. His grandfather cooked for Stalin as well as for Lenin and Rasputin. Any connection with a Czar was a ‘golden thread to power’. Putin, Montefiore believes, can be seen as a hybrid of two modernities – the Romanov tradition and the Soviet tradition.

Overall, a fascinating panel!

Perth Writers’ Festival 2016

18 – 21 February